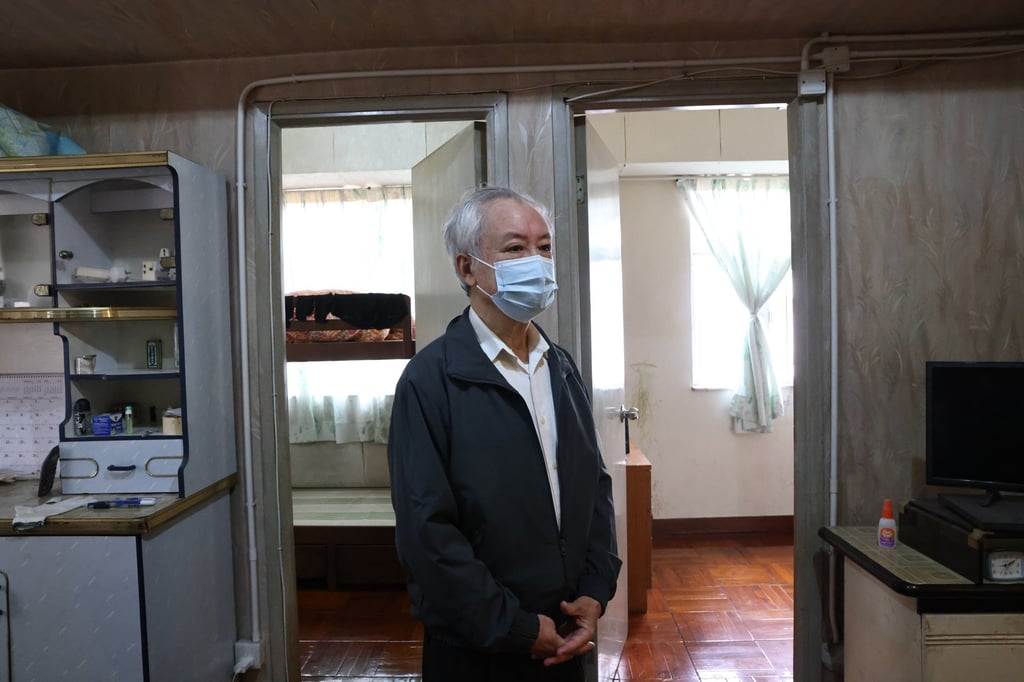

For Joseph Ng Goon-lau, dubbed the “king of haunted flats”, these stigmatised properties represent a lucrative investment.

Ng has mastered the art of buying and selling homes where unnatural deaths have occurred, and he offers a rare glimpse into a market shaped as much by fear as it is by opportunity.

His foray into the “haunted” properties market began in 1993 when a worker died in an accident in one of his flats. The incident made the flat nearly impossible to sell, even at a discounted price. He did, however, eventually find a buyer.

Foreigners are quite happy to rent a haunted [property] because they don’t understand Cantonese, so they don’t think the ghost will talk to them

“This tells me that one can succeed in selling a bad property if he has patience,” Ng says. His experience highlights a significant aspect of the “haunted property” market: how patience and a strategic approach can turn an ill-fated investment into a profitable one.

“Foreigners are quite happy to rent a haunted [property] because they don’t understand Cantonese, so they don’t think the ghost will talk to them,” Ng explains.

In Hong Kong, the aftermath of a violent death can have a profound impact on property values. Flats where such incidents occur can be bought for between 10 per cent and 30 per cent below market price.

The stigma can also spread to neighbouring flats, and even to all the flats in the building, and drastically lower their market value too. This phenomenon, known as the “calamity house” effect, reflects the deep-seated superstitious beliefs that many Hongkongers hold.

Ng believes that such properties will always attract interest if the price is low enough, but stigma is something that cannot be easily erased.

Dragon Lodge on Victoria Peak is one of the most famous “haunted houses” in Hong Kong. Its eerie history and abandoned state have made it a favourite subject of local legend and ghost stories.

The mansion, which last sold for HK$74 million in 2004, is rumoured to be haunted by the ghosts of Catholic nuns who were executed there by Japanese soldiers during the second world war. It has been deserted for decades, with onlookers only able to view the home from a distance on Lugard Road.

There is no legal requirement for property agents in Hong Kong to voluntarily disclose to potential buyers any deaths that have occurred at a property. However, according to the legal principle of caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), if a potential purchaser or tenant asks about the history of a property, the agent must find out and pass on as much information as possible about it or they could be guilty of misrepresentation.

Such a requirement for transparency adds another layer of difficulty when it comes to selling such flats.

Still, as Ng says: “The higher the risk, the bigger the return.” This mindset is what drives him and other investors to continue dealing in so-called haunted properties.

Another obstacle to selling such properties is that Hong Kong banks are often reluctant to provide mortgages for them. Sellers must therefore find buyers willing and able to pay cash, which further shrinks the pool of potential purchasers.

Ng recalls an instance where he managed to secure a mortgage by proving that a death did not occur inside the flat but rather in a hospital, thus convincing the bank that the property was not technically a hongza.

While there will always be those, like Ng, who see value in these stigmatised flats, the broader market is less enthusiastic.

The house where Choi’s remains were found in 2023, for example, may eventually find tenants or a buyer, but this will take time, and the price will probably be far below its market value.

As Ng’s experience shows, there is a market for these properties, but it is one that requires patience, understanding of cultural nuances and a willingness to take on risk.