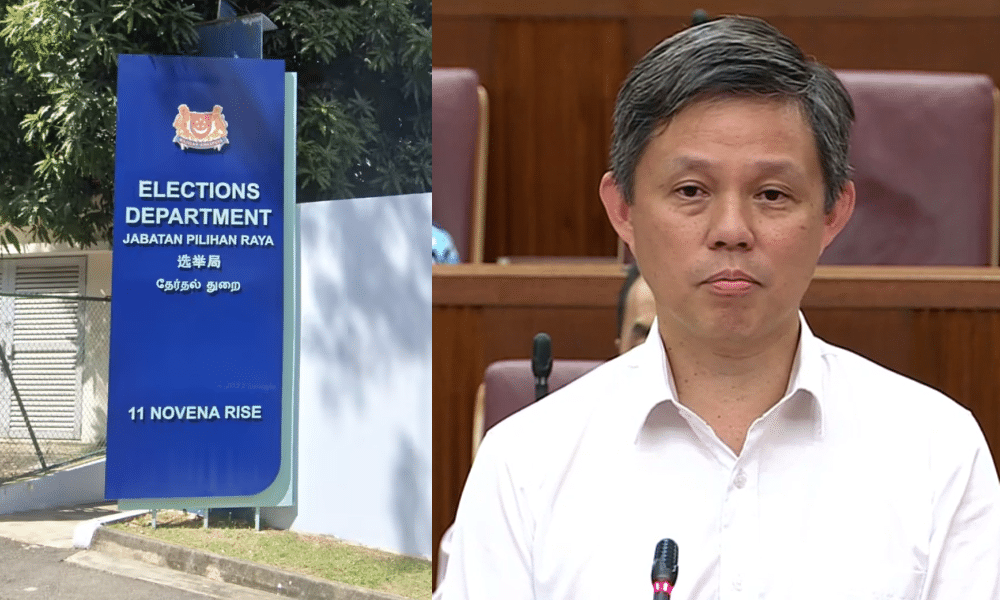

In Parliament on 7 August, Education Minister Chan Chun Sing made a non-statement that might have inadvertently revealed more than intended.

During a motion debate raised by the Progress Singapore Party’s (PSP) Non-Constituency Members of Parliament (NCMPs), Mr Chan addressed statements made by members of the opposition about Singapore’s electoral boundaries, a topic that has long been a subject of public suspicion and concern.

PSP NCMP Mr Leong Mun Wai, speaking on the motion, questioned the irregular shapes of certain constituencies and the seemingly arbitrary splitting of Housing Development Board (HDB) towns across multiple constituencies.

Mr Leong cited examples like Braddell Heights, where he lives, being part of Marine Parade GRC, and questioned the rationale behind the frequent changes in constituency borders experienced by residents.

In response, Mr Chan merely reiterated that the motion was about the process of boundary drawing rather than specific decisions made by the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC). He clarified that he had no influence over the EBRC’s decisions and emphasized that the focus should be on maintaining an apolitical process.

Mr Chan, speaking on behalf of the Prime Minister, asserted that electoral boundaries are drawn to serve the interests of the people, not political parties.

Yet, when pressed for a direct answer on whether gerrymandering occurs in Singapore by the Leader of the Opposition, Mr Pritam Singh, Mr Chan demurred, leaving his response open-ended and ambiguous.

Mr Singh asked, “Is there gerrymandering in Singapore?”

In response, Mr Chan said, “I think I’ve explained the meaning of gerrymandering, what it means in other countries, and whether it applies or does not apply in our context. And I’ll leave it to members of the House and the public to decide.”

This refusal to answer a straightforward question could be seen as a warning sign. Under Singaporean law, while statements made in Parliament are generally protected from liability, false representation of facts can still lead to consequences under the Parliament (Privileges, Immunities and Powers) Act.

If Mr Chan had been aware that gerrymandering had indeed taken place in Singapore and had falsely presented this knowledge to Parliament, he would have risked severe repercussions.

This legal risk could explain why Mr Chan avoided giving a direct answer. His hesitation might suggest that acknowledging the absence of gerrymandering could expose him to legal jeopardy if evidence to the contrary were ever made public. The same reason why Dr Vivian Balakrishnan saw the need to clarify the assurance he made to Parliament over the use of data in the TraceTogether app, which he had previously promised would be used only for COVID-19 tracing purposes.

What is also telling is that despite the political significance of this issue, no other members of the People’s Action Party (PAP), including the Prime Minister, chose to address the motion from the PSP.

This silence speaks volumes, suggesting that Mr Chan may not be alone in his reluctance to tackle the question head-on. The fact that the Prime Minister — both current and former — and other senior members of the PAP who were present at the motion did not engage in the debate might imply that they, too, would struggle to provide a straightforward answer without risking contradiction or legal implications.

Adding weight to the suspicions of gerrymandering is a recollection shared by veteran journalist Bertha Henson.

In a Facebook exchange with Andrew Loh, co-founder of The Online Citizen, over PSP’s motion, she recalled a conversation with Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong, who was then Prime Minister, in which he reportedly said that he would ask the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC) to redraw boundaries to facilitate a direct contest between Dr Chee Soon Juan, Secretary General of the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP), and then-Minister of State Matthias Yao of the People’s Action Party at Marine Parade GRC.

A version of this arrangement was recorded in a report in The Straits Times on 3 October 1994.

The report stated, “He (Mr Yao) said he had sought and the Prime Minister had agreed to propose to the proper authority to have his MacPherson ward detached from Marine Parade GRC for this straight fight.”

There does not appear to be any public record of ESM Goh refuting this news.

Furthermore, a Straits Times report on the EBRC’s report in November 1996 explicitly stated that the Mountbatten Single Member Constituency (SMC) was being carved out from Marine Parade GRC so that Dr Chee and Mr Yao could have a straight fight between them, seemingly supporting the notion that the Prime Minister does exert influence over the EBRC’s decisions.

With the above in mind, Mr Chan’s defence that the Prime Minister has no influence over the EBRC’s boundary reviews seems awfully difficult to reconcile with this historical precedent.

Let’s not also forget that the members of the EBRC are top civil servants appointed under the recommendation of the Prime Minister.

The composition of the EBRC committee has historically been comprised of:

- Secretary to the Cabinet, who typically also serves as the Prime Minister’s Principal Private Secretary

- Chief Executive Officer of the Housing and Development Board

- Chief Executive of the Singapore Land Authority

- Chief Statistician, Department of Statistics

- Head of the Elections Department, who reports to the Prime Minister

Given this context, it is reasonable to question whether the committee operates independently of the Prime Minister’s influence or whether it is swayed by the political objectives of the ruling party.

Even setting aside the question of whether gerrymandering is actively practised in Singapore, the way electoral boundaries are drawn undeniably raises eyebrows among voters who have seen changes to their constituencies in general elections, despite residing at the same address for decades.

The frequent redrawing of boundaries, often resulting in changes that appear to benefit the incumbent PAP, does little to dispel suspicions of gerrymandering. For instance, the removal of SMCs that the PAP nearly lost in previous elections could be interpreted as a strategy to secure electoral advantage and create an issue for alternative political parties to campaign as they are uncertain how the boundaries would be redrawn.

An explicit example of this is the case of Joo Chiat SMC, where former WP NCMP Yee Jenn Jong won 48.98% of the vote in GE2011. Mr Yee was awarded an NCMP position because of the high percentage he received and later worked hard to campaign in the SMC over the next few years.

However, in GE2015, the SMC was absorbed into Marine Parade GRC, forcing him to form a team to contest in the GRC, which the National Solidarity Party had contested in the previous election — another issue arising from the arbitrary redrawing of electoral boundaries.

For larger parties like the PSP and the Workers’ Party, countering the potential redrawing of boundaries may involve contesting neighbouring constituencies so that even if there is a redraw, the party will still be in the running.

Ironically, this approach could eventually turn the practice of boundary redrawing against the ruling party itself, as seen in the case of Sengkang GRC, where the PAP lost three of its officeholders.

At its core, politics is about serving the people, and the belief that the PAP may be redrawing boundaries for its political gain undermines public trust.

For many years, the social compact between the PAP and Singaporeans has been one where citizens overlook these perceived manipulations in exchange for prosperity and stability.

However, as job opportunities, including newly created positions, seemingly go in the way of foreigners (including Permanent Residents)—as shown in the latest labour report—and the cost of living continues to rise, particularly for younger generations in their apparent struggle to afford new homes, this compact is showing signs of strain. The next general election could see this trust re-evaluated, along with the acceptance of the perceived practice of gerrymandering.

Mr Chan’s non-reply to the question of gerrymandering in Singapore might not be a smoking gun regarding whether gerrymandering takes place in the city-state, but it certainly raises more questions than it answers.