Political undertones aside, it is a ripping yarn that hooks the reader from the first page with its thrilling account of wolves chasing their prey. The Penguin executives made a bid for the book there and then, putting forward US-dollar figures that left Lusby wide-eyed.

I only take on things if I believe there is a future audience for it

Jo Lusby

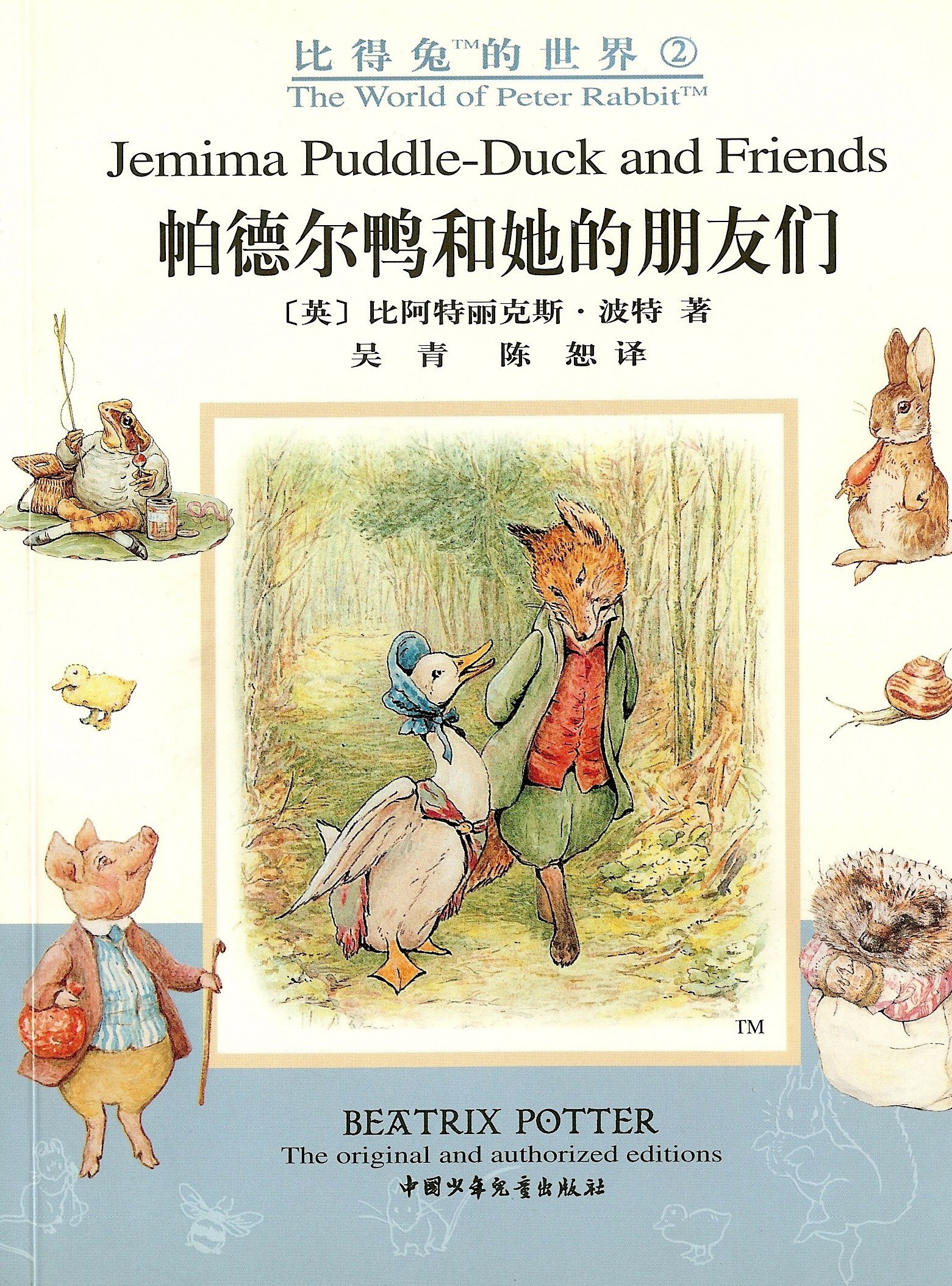

It was the launch pad for a career that has seen her overseeing the publication of former United States first lady Michelle Obama’s memoir, classic books from the extensive Penguin back catalogue and various bestselling children’s titles such as Peppa Pig, Charlie and Lola, Peter Rabbit and Spot the Dog.

“My bosses were convinced it was a beautiful story,” says Lusby. “They then said they could offer ‘US$100,000 right here, right now’.

“They told the author and agent, ‘If you want more, then we would have to go back and go through the formal appraisal process.’ They all looked at each other briefly, and the author nodded vigorously and said, ‘OK!’

“As we left, one of my bosses turned to me and said, ‘You have just bought a book.’

“It did very well internationally. From its first English-language publication, in 2008, to 2012, it was the highest selling work of Chinese literature in English. That is my estimate.

“It was a New York Times bestseller and the wider international rights did well. It has been massively surpassed by The Three-Body Problem since then.”

“With anything like Midnight in Peking, when you work on it all the way through it is less that you are surprised by its success, but gratified,” says Lusby.

“I only take on things if I believe there is a future audience for it. It is such an unpredictable curve; so many things can go wrong but if something resonates it is very fulfilling.

[Penguin’s] vice-president of marketing in the US had been to China and he became obsessed with Midnight in Peking. When he got behind it, it felt like the wheels of momentum were rolling.”

A 23-year-old Lusby found her first job in China in 1998, working as a teacher at Nanjing International Studies University, a role that included appearing before classes of uniformed People’s Liberation Army soldiers, armed with a brief to upgrade their English and give a broader perspective on the outside world.

Self-taught fluency in Mandarin, with an ability to read and write characters to an advanced level, made Lusby an attractive hire for Penguin, as well as being handy tools for negotiating daily life.

A later project was running a bilingual entertainment magazine, listing the limited nightlife options in Nanjing, a position that later led to an offer from an English-language Beijing lifestyle magazine in 2000 and, ultimately, the Penguin gig, and then a move to Hong Kong, where she now runs her own consulting agency for authors, Pixie B.

“My old boss at City Weekend magazine had a philosophy that in Beijing at that time you could be anything, regardless of your background,” she says.

“Beijing is one of those cities that gives itself up bit by bit – you are always finding other layers, communities and areas.

“It felt as though we were at the centre of something very important and it was rewarding, hard to separate work from social life. You were talking daily to thinkers and writers.

“We didn’t realise then that it was a brilliant time to be there. We didn’t appreciate how lucky we were.

Lusby, now 49, was able to capitalise professionally on the emergence of China’s affluent middle classes: internationally curious consumers who were willing to spend money on authentic books rather than badly printed knock-offs.

After joining Penguin in 2005, she presided over a growth from zero to 250 titles released annually, including the autobiography of tennis star Li Na, who attracted long lines of young men at book signings.

I have always been an avid reader and have an English literature degree but I didn’t know the book industry. Penguin said, ‘You teach us China, we will teach you books.’

Jo Lusby

Another job was to promote the novels of Nobel Prize for Literature winner Mo Yan internationally.

“His writing is not negative about China, but it is not flattering either,” she says. “It is an honest portrayal of his own experiences.

“He got it from both sides. Because he was not a dissident, living in Beijing, and member of the Chinese Writers’ Association, there was this perception in the West that he was a stooge, a patsy and his writing was somehow compromised because he was not independent from the government.

“He gave an interview and was asked about censorship and he said it is not always bad, he said there needs to be a harmonious society. That played badly in English but I have a lot of sympathy for him because you have to be pragmatic living in China.”

Working in Beijing for so long made Lusby deeply aware of such sensitivities; it was one of the reasons Penguin appointed her general manager in China, later to become managing director, North Asia, despite no previous experience in the world of bookselling.

There were numerous caustic remarks from expatriates in the media world, cynical naysayers who suggested Lusby might be out of her depth.

“I have always been an avid reader and have an English literature degree but I didn’t know the book industry,” says Lusby. “Penguin said, ‘You teach us China, we will teach you books.’”

With the fast-talking, eloquent Lusby the anecdotes flow freely.

Some of the most amusing are a little too delicate to publish, but on-the-record stories about politics and business in modern China are likely to emerge in a forthcoming memoir by outspoken and well-connected executive Jörg Wuttke, who spent more than three decades as a senior executive in China, most recently with German chemical company BASF, and served as president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, before a planned move this summer to the United States.

That book is part of a mixed portfolio in the stable of Pixie B, the Hong Kong company owned by Lusby and her South African wife, Michelle Lombard, the chief financial officer and strategic adviser.

For me [Lusby] was an editor and a publisher and a lawyer and an agent all wrapped up in one

Paul French, the author of Midnight in Peking

Pixie B acts as the exclusive agent for Harry Potter digital products in China, a role that has a strong focus on ensuring Chinese licensees do not tamper with author J.K. Rowling’s work.

The rules were bent slightly, to allow multiple narrators for the audiobooks, rather than the single voice that is more common in the West.

The entire series of seven books has now been committed to audio with each title available for subscription, at around HK$10 (US$1.30), not a huge amount until you factor in China’s population of 1.4 billion.

The role of Pixie B is to act as agent for The Three-Body Problem’s international content deals, beginning with audio drama content.

An instinctive nose for a quirky project led to the signing of a young social-media influencer based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, who Lusby met at a book fair.

Thai illustrator Sean B. Hiran has a digital following of 2.5 million and a proposed book, still in progress, titled The Three Friends of Winter, will feature inspirational life lessons told through a trio of cute animals.

Pets feature prominently in the life of the entrepreneurs; two dogs and two cats share their home in Mui Wo, on Hong Kong’s Lantau Island, where they host regular rooftop gatherings.

French, Midnight in Peking’s London-based author, neatly summarises Lusby’s professional and social skills. “For me she was an editor and a publisher and a lawyer and an agent all wrapped up in one,” he says.

His latest book, Her Lotus Year, about Wallis Simpson, due out in November, is another untold China story, documenting the future Duchess of Windsor’s time in the country.

“Lots and lots of people were encouraged by Jo. People were always sending in manuscripts,” French says.

“The expat memoir is not a fantastic genre but there are always people who want to write and she was very encouraging, giving advice, from foreign correspondents who ended up doing really good books to people who were just bumming around.

“Beijing is such a small and febrile expat community, so saying no to people was always a little bit tricky as you could bump into them.

“If you were to ask Jo, she probably felt confident in my research skills and my knowledge of the world that I was writing about, but I don’t know for sure that she was confident of my literary skills, nor was I particularly. She gave me the room to work my literary chops.”