It feels a little crazy to have taken a long, expensive trip to see one of the world’s most remote inhabited islands.

Visitors not arriving by cruise ship fly in from Santiago, Chile’s capital city, on Latam Airlines, the only airline currently serving the island.

The palm trees and sea breeze outside the airport, which has a thatched roof decorated with bird motifs, make it feels as though you have left Chile for Polynesia – which is where the island’s original settlers came from, sometime between 400AD and 800AD.

They developed their culture in isolation until Easter Day, 1721, when Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen stumbled upon the small, triangular island.

The airport is in the island’s only town, Hanga Roa, where about 95 per cent of Rapa Nui’s 8,000 inhabitants live.

A collection of low buildings, some with thatched roofs, beside a harbour, Hanga Roa is most definitely a tourist town, with lots of tour agencies, restaurants, outfitters and large handicraft and souvenir markets.

Elsewhere, at the Holy Cross Church, the Virgin Mary statue wears a crown of birds, the Holy Spirit is represented as a frigate bird rather than a dove, and people sing hymns in the Rapa Nui language.

My four-night stay at the all-inclusive Explora Rapa Nui lodge, 6.5km northeast of Hanga Roa, includes a sea-view room, meals full of fresh vegetables – more than I would have expected to be served on a remote island – and daily guided excursions, such as hiking, biking and snorkelling.

Visitors who crave more autonomy can rent a car or bicycle to get around the hilly, 164 sq km (63 square mile) island. The roads are not busy but they are bumpy and can be slippery after rain, so biking is recommended for experienced cyclists only.

Moai tower over us in various states of completion, staring through empty eye sockets. The largest lies gazing skyward, 22 metres (71 feet) long, his face clearly visible, his back still attached to the hillside.

Each moai depicts a leader, his stone figure watching over his village after he dies. The biggest Rapa Nui mystery is how these giant sculptures – which weigh an average of 12.5 tonnes (13.8 tons) – were moved from the quarry around the island.

Guide Ricky Clementi passionately defends the theory that groups of men wrapped ropes around moai and used momentum and a rocking motion until the statues seemed to be walking.

I have brought water shoes instead of hiking boots and am disappointed when the sea is deemed too dangerous for diving and snorkelling, which is a fairly common occurrence. Every day of my stay becomes a hiking day (trainers sufficing), and every hike takes in Rapa Nui culture.

My tour groups never number more than seven people, and we travel by van across the island. Explora arranges outings at less busy times of the day, so nowhere feels crowded.

Almost half of the island is designated a national park, in which visitors are required to have a guide. Good ones make all the difference; many tourists must leave Rapa Nui feeling like an anthropologist.

Piles of rocks are seldom just piles of rocks. Instead, they are the foundation of a boat-shaped sleeping structure, or a stone chicken coop, or a primitive observatory.

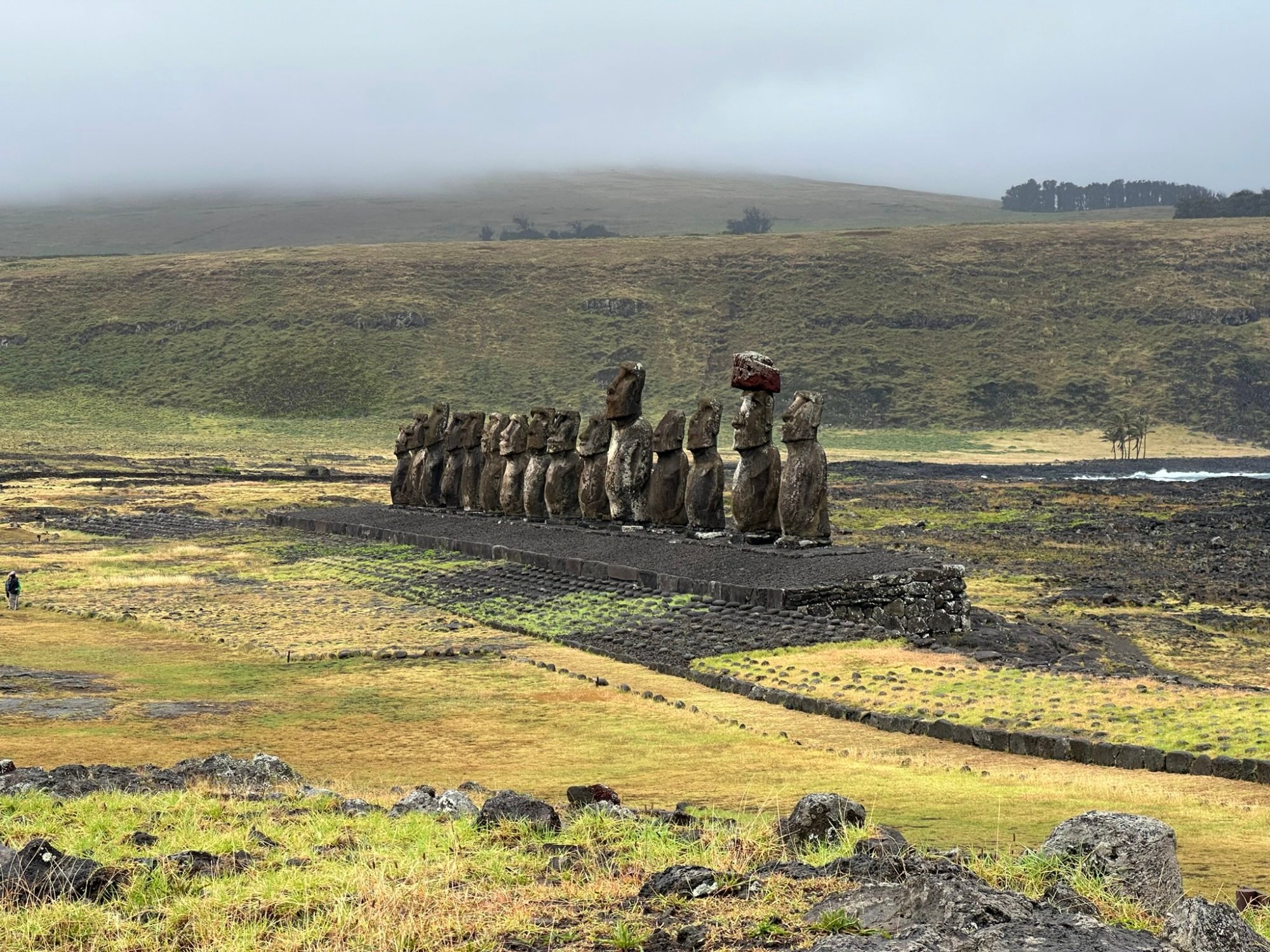

Fallen moai lie face down across the island. They had all been knocked over by the early 1800s, but some have been restored to an upright position.

Twenty-something guide Eka tells us that almost half of today’s islanders are descended from the early Polynesian settlers.

Since the population reached a low of 111 in 1877 – reduced by war, slave raids from South America and exposure to Western diseases – intermarriage has been rife. Every time he liked a girl in school, says Eka, she turned out to be his cousin.

“That’s the story of my life,” he says, shaking his head.

Easter Island came to the world’s attention in 1962 when pictures of moai appeared in National Geographic magazine. “Massive heads carved of stone stand vigil on this island so remote, that the only visitors arrive aboard the annual supply ship,” the accompanying article said.

Sixty years later, in 2022, arrivals had surged to 100,000 a year. With the tourists came a new interest among Rapa Nui people in their culture and in preserving their language.

As we stand looking at seven restored moai at a site called Ahu Akivi, guide Isabel Icka says her mother’s generation, born into tourism, feels a much stronger connection to the moai than her grandmother ever did.

Although our guides deliver authoritative-sounding information, much of it is speculative and some questions remain unanswered – which Polynesian island did the original settlers come from? Why were the moai knocked down? And what was that triangular black craft Eka claims he and other islanders saw hovering over the volcano crater early one morning?

They only add to the allure of a destination that is ideal for lovers of a good mystery.

The writer’s stay was provided by Explora Rapa Nui.