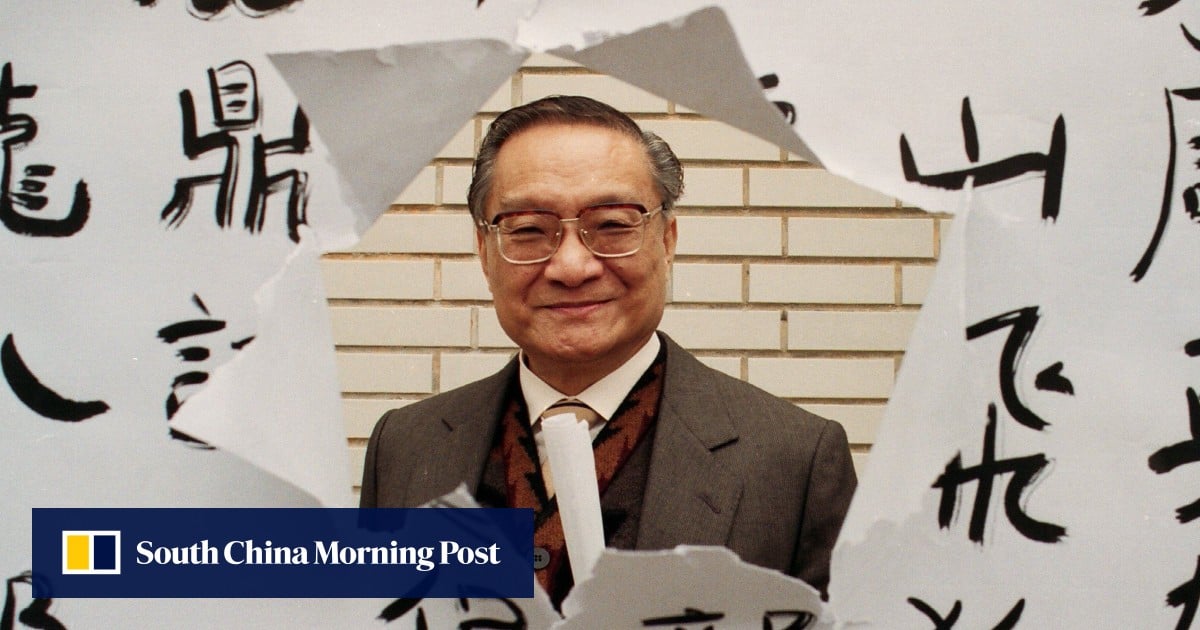

Another of those novelists – Chen Wentong, better known by his pseudonym Liang Yusheng – is also having the centenary of his birth celebrated this year.

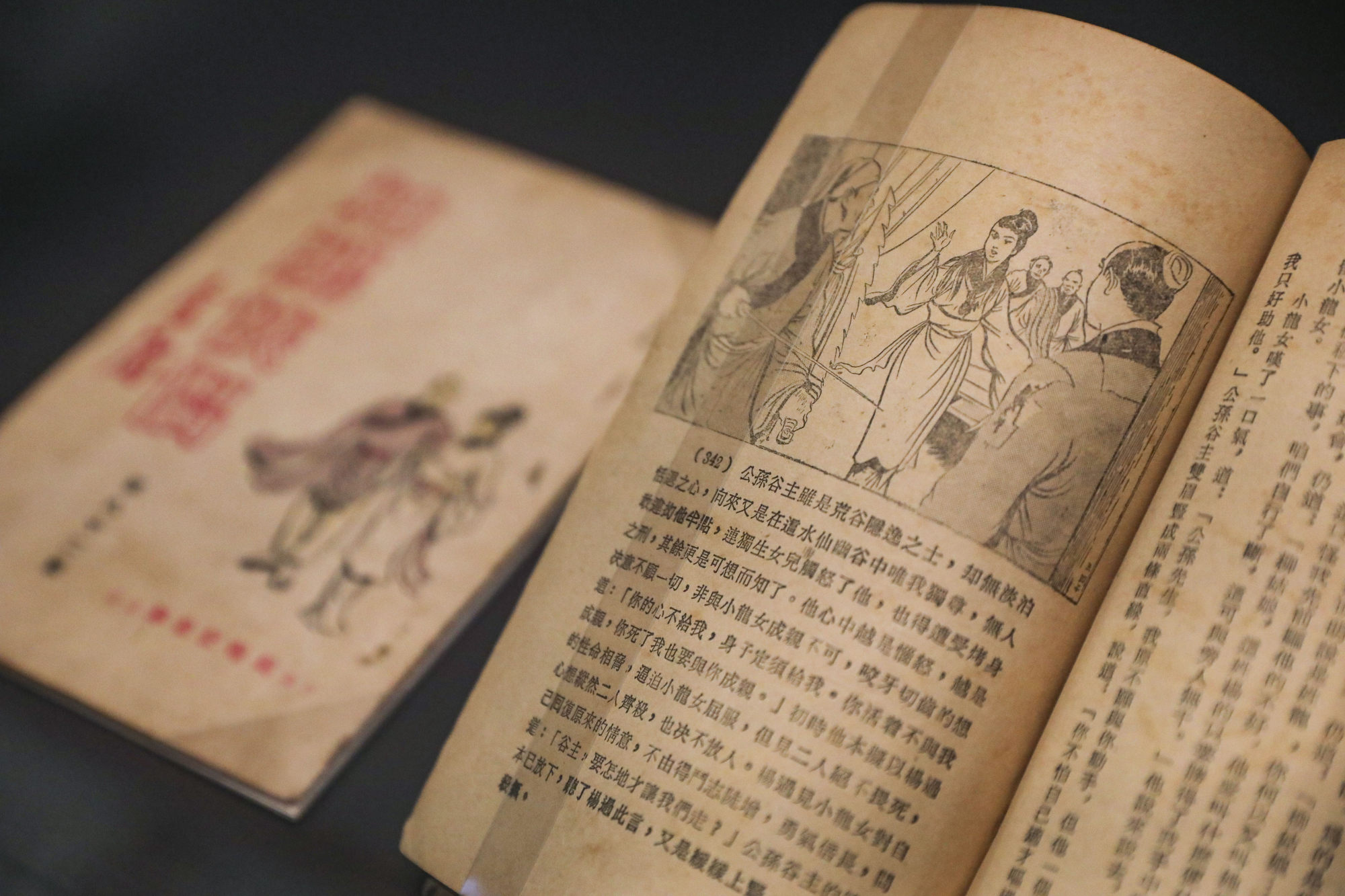

Born into a scholarly family in Haining, in China’s Zhejiang province, in 1924, Cha was always an avid reader. It is said that he discovered the wuxia genre, which was very new at the time, at the age of eight, after reading Huangjiang Nüxia (The Swordswoman of Huangjiang) by Chinese novelist Gu Mingdao (1897-1944).

In 1948, Cha graduated from Soochow University in Shanghai at the age of 24 with a degree in international law, before moving to Hong Kong to join the Chinese-language newspaper Ta Kung Pao.

Two years later, he became an editor of the New Evening Post, the evening edition of Ta Kung Pao, and met Chen.

Like Cha, Chen was also born into a scholarly family, and grew up in a village in Mengshan county, in Guangxi province. He, too, moved to Hong Kong, in 1949, and quickly found work in Ta Kung Pao.

As colleagues, Cha and Liang pioneered a new era of wuxia interest in the mid-1950s as they prolifically published serials in their shared column “Three Swords House” in the New Evening Post. When the column ceased in 1957, both organised their published stories and released them as novels, while continuing to write.

Chen’s Pingzong Xiaying Lu (1959-60) was said to be at the forefront of the new school of wuxia novels at the time. His other famous works include Qijian Xia Tianshan (1956-57), which inspired Hong Kong director Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005); and Baifa Monü Zhuan (1957-58), which was adapted into The Bride with White Hair (1993), a Hong Kong cinema classic directed by Ronny Yu and starring Brigette Lin Ching-hsia and Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing.

But it was Cha who reigned not only in the world of Chinese literature but also Hong Kong pop culture with his beautiful writing and addictive stories.

The Legend of the Condor Heroes (1957-59) was the source of inspiration for director Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time (1994); while his final and longest novel, The Deer and the Cauldron (1969-72), has been the subject of many TV adaptations over the years, with its main character, Wei Xiaobao, played by actors including Tony Leung Chiu-wai.

Chen’s writing heavily references history and elements of traditional Chinese poetry and literature, and his heroes tend to be versatile and well-read. Cha, who was also influenced by Chinese history and culture, penned chivalrous but solitary protagonists who obsessively devote their lives to the craft and philosophy of Chinese martial arts.

This difference perhaps had to do with how the wuxia literary giants chose to lead their lives. For most of his career, Chen focused on writing novels, columns, critiques and essays before he migrated to Australia with his family in 1987, where he converted to Christianity at age 70 in 1994.

Cha, on the other hand, had more of a rebellious and entrepreneurial streak. He co-founded the Hong Kong-based Chinese-language newspaper Ming Pao in 1959 and began to criticise Communist China’s policies around 1964.

He was also outspoken against the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and during Hong Kong’s 1967 leftist riots, which saw him receive death threats. In 1985, he was a founding member of the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee, but resigned in 1989 in protest against Beijing’s martial law that led to the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

In 1998, Cha and Daisaku Ikeda, a Japanese philosopher and author who was awarded the United Nations Peace Medal in 1983, co-wrote Compassionate Light in Asia, a series of intellectual discussions between the two, published in both traditional and simplified Chinese as well as Japanese.

In the book, Ikeda wrote of Cha: “I marvelled at his strength of character in the face of immense power … This is the ‘grandmaster’ spirit that has been passed down through thousands of years of Chinese history … Mr Jin Yong used his pen as a sword, shining sharply.”

In 2004, Cha received an honorary doctorate from the University of Cambridge, in England. The following year, the writer left Hong Kong for the UK to study at the university for a non-honorary doctorate, and received a PhD in 2010 for his thesis “The Imperial Succession in Tang China, 618-762”.

Chen died on January 22, 2009 in Sydney, Australia, aged 85, while Cha died on October 30, 2018 in Hong Kong, at 94.

Their legendary status in the Hong Kong literary world remains undisputed, while their works continue to be widely revered in the larger Sinosphere and diasporic Chinese communities around the world.

“Sculpture: Guo Jing”, Terminal 1 Arrivals Hall, Hong Kong International Airport, 1 Sky Plaza Road, Chek Lap Kok. Open 24/7. Until July 19.

“Sculpted by Ren Zhe”, Hong Kong Heritage Museum, 1 Man Lam Road, Sha Tin. Open 10am to 6pm on weekdays (closed Tuesdays), 10am to 7pm on weekends and public holidays. Until October 7.