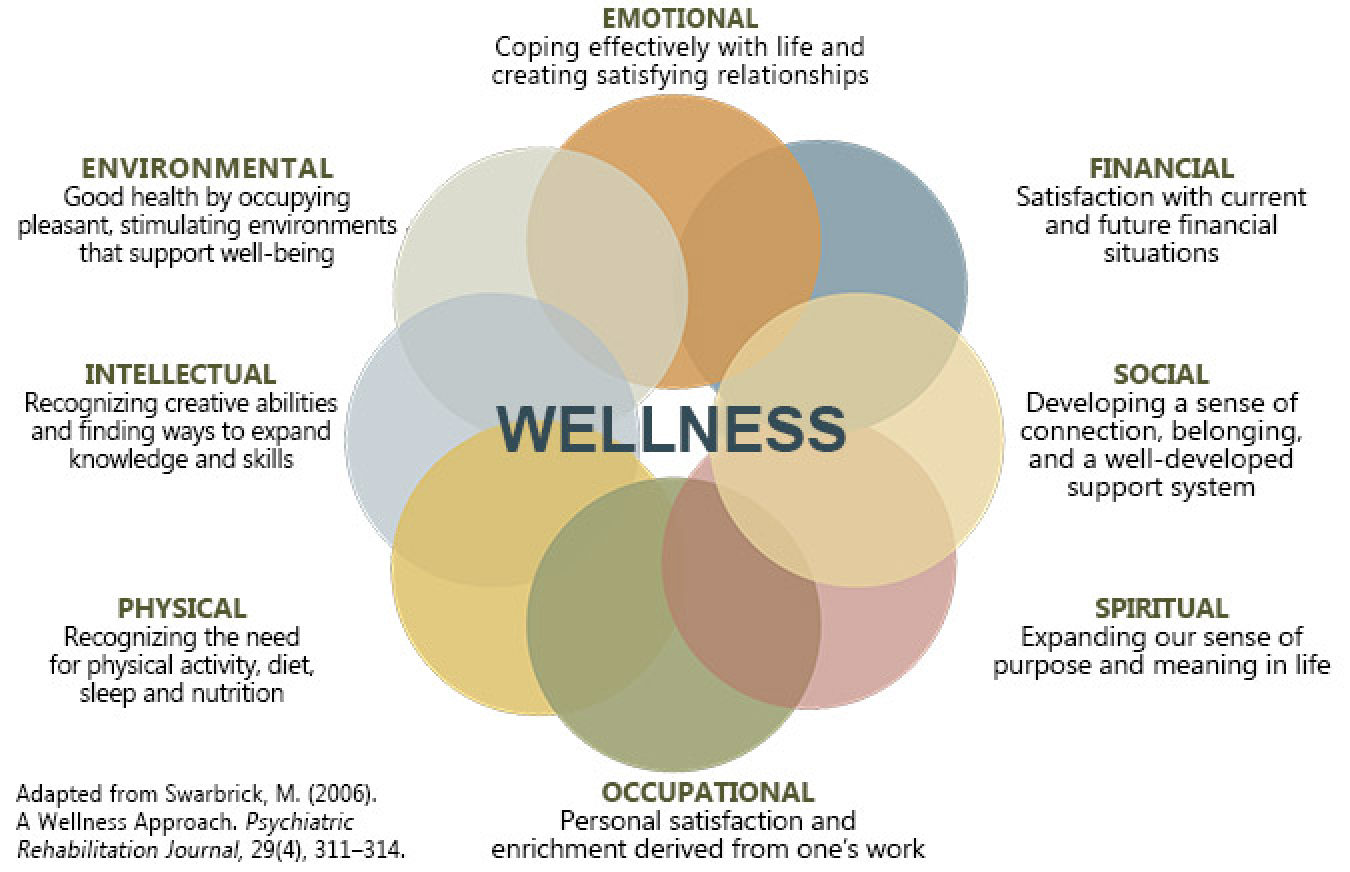

In the 1990s, Dr Peggy Swarbrick, a research professor in psychology at Rutgers University in the US state of New Jersey, introduced the “Eight Dimensions of Wellness” model, which encompasses emotional, financial, social, occupational, physical, intellectual, environmental and spiritual well-being.

What makes Swarbrick’s model insightful is the way these dimensions intersect. For instance, spiritual wellness overlaps with social connections – “a sense of belonging”, and occupational fulfilment – “enrichment from work”.

“In the end, everything will fade, and my body will no longer be here. That’s why I chose titanium – to me, this is much closer to eternity,” says the 68-year-old.

His work Transcendence partly comprises four 10-metre (33-foot) titanium sculptures suspended from the chapel’s ceiling. It is, he says, his attempt to push beyond the confines of space and time, to transform conflicts into opportunities for growth and enlightenment.

“My pursuit always centres on transcending struggle, difficulty, misery and pain,” Chan reflects. “By doing so, one attains a state of calmness and peace. That’s the essence of my creations.”

You only have this one moment in your hand to make something out of, to build your life on. It is about entering the moment and knowing the value of your time

His determination to impress his boss and retain his job fuelled his journey towards artistic mastery.

“I had to be good at my work because my work could give me an identity,” says Chan. “And then it became a search for skills and knowledge and learning how to communicate with my materials in the years after.”

Years of introspection, immersed in his craft, led him to create the Wallace Cut – an illusionary three-dimensional carving technique – in 1987. This process, he says, transcended mere craftsmanship; it was a fusion of mind, heart and hands, as if the very materials ceased to exist – a state of perfect existence.

He sees life divided into an “outer world” – that which you observe and will either attract or repel you – and an “inner world” which is discovered when you look inside yourself. Fully accessing that second world takes much practice but offers great rewards.

“When you look inward, you are starting to practice, you are starting to control your desires and let go of your desires, and that is when you get your inner strength,” says Chan.

“When I carved, it felt like an almost religious practice – a dialogue between my tools and the raw materials. As a monk, I was able to put what I experienced in words,” he says. “I couldn’t have expressed it in terms of spiritual reality before.”

Spiritual well-being may include religious practices, but it is more about a broader sense of purpose, connection and inner peace.

“Both religions have done something to me in my life, making small changes and big changes, so I am always in between these two religions. To me, both church and temple are … sacred places. I will come into a church with respect and come into a temple with respect,” says Chan.

He makes a bold statement about the similarities he sees between the two religions in Transcendence. The suspended sculptures are joined by two smaller ones on an altar: one of Jesus and one of Buddha – but Chan has swapped their heads.

“The creative process is a constant process of self-reflection. And it is also constantly looking for purpose and meaning and connection and transcendence. It enhances my spiritual well-being,” says Chan, who hopes the exhibition can provide a spiritual art experience, “some sort of spiritual elevation”, to the viewer.

A transcendent experience takes us out of ourselves and allows us to connect to something larger, often giving us a greater sense of purpose and meaning.

We can take some tips about spiritual well-being from Chan, but the life of an artist is not necessarily a well-rounded one. When working on a project, he works long hours, often skipping sleep to spend time with his sculptures.

Transcendence is on display until September 30 in the Chapel of Santa Maria della Pietà in Venice.