Disclaimer: Opinions expressed below belong solely to the author.

On November 30, 2022, the day OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public, we were thrust into a completely new reality — though not an unfamiliar one, given how many sci-fi novels and movies predicted that one day we would be conversing with intelligent machines.

Launched around the same time, diffusion models showed us that computers can learn to generate imagery at will, followed by increasingly more sophisticated video footage, as recently exhibited by OpenAI’s Sora.

Quite overnight, computers have been granted powers to do things that thus far only humans could do — create, speak, design, draw, and write.

Since then, the AI craze has taken over the world. We’re discussing how and when robots will take our jobs, making millions of people redundant, before conquering the planet and threatening our very existence.

On their way to total dominance they appear to have already conquered the world of business. A seemingly endless stream of billions of dollars is being poured globally into companies building competing AI models and the hardware necessary to run them.

And everybody wants to get a piece of the pie.

Not only are we now getting laptops or smartphones with AI features, but also AI vacuum cleaners and lawnmowers. Millions of inanimate, electronic devices seem to be acquiring reasoning skills which are expected to turn our world upside down within a few short years.

Some experts in the field make bold predictions that Artificial General Intelligence — machines with reasoning capacity equal to human beings — could arrive in as little as three to eight years.

Even Nvidia’s CEO, Jensen Huang, predicted that AI would be able to pass all human tests within five years.

However, if history teaches us anything, we might be in for a much lengthier wait.

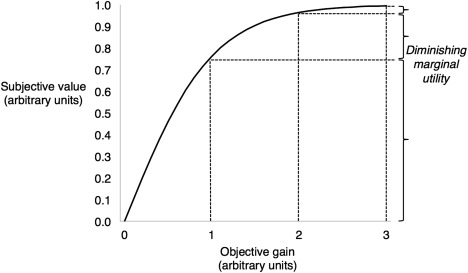

Law of diminishing returns

With the dawn of AI-enabled washing machines and refrigerators, I think it’s worth to pause and think if we’re not getting ahead of ourselves.

The nature of technological development is that it typically starts with a breakthrough before gradually tapering off as evolution and refinement of the new invention inevitably take more and more time. There is no reason why AI should be different.

Think of it this way — the first slice of pizza usually provides the most satisfaction. You get quite a lot of it with your second or third slices as well. But at some point in satisfying your hunger each bite you take will provide less and less gratification — less “marginal return” or “marginal utility”.

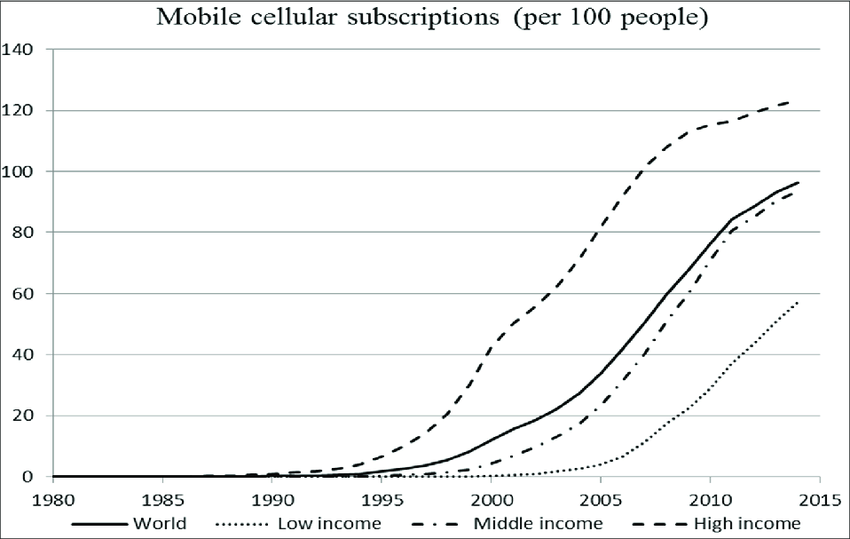

Remember how 5G was promoted as the next big thing in technology? But how many of us have really noticed any difference? 4G was good enough for the vast majority of everyday uses. 3G was a huge leap in performance over 2G, which in turn provided the largest marginal leap by making the web reasonably accessible on mobile devices for the first time.

Life-changing technological developments have always needed enormous effort, even if the path was clear to engineers and investors.

They also require a lot of time.

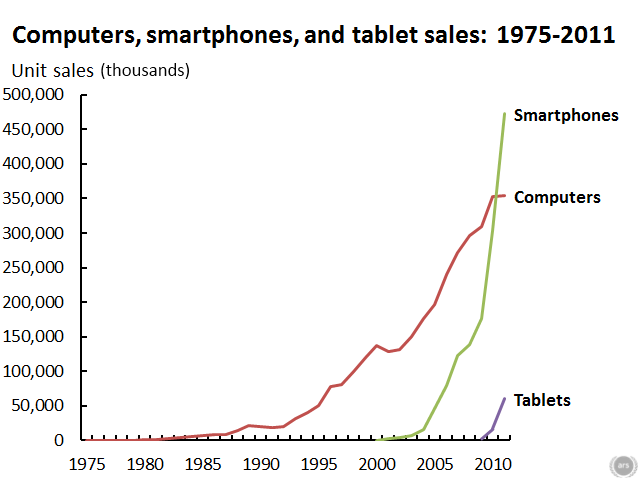

It had taken 25 years for general-purpose computers to leave military compounds and universities, making their debut in people’s homes in the early 1970s, and another 40 years before reaching global saturation.

These days, they are overtaken by personal, mobile devices such as smartphones, which can perform many of the same functions.

On the topic of mobile phones, the world’s first launched in 1983, but it had taken another 20 years for it to become an ubiquitous device even in the developed world.

Today, most humans have a smartphone in their pockets, a technological “revolution” which has, however, needed four decades to fully unfold.

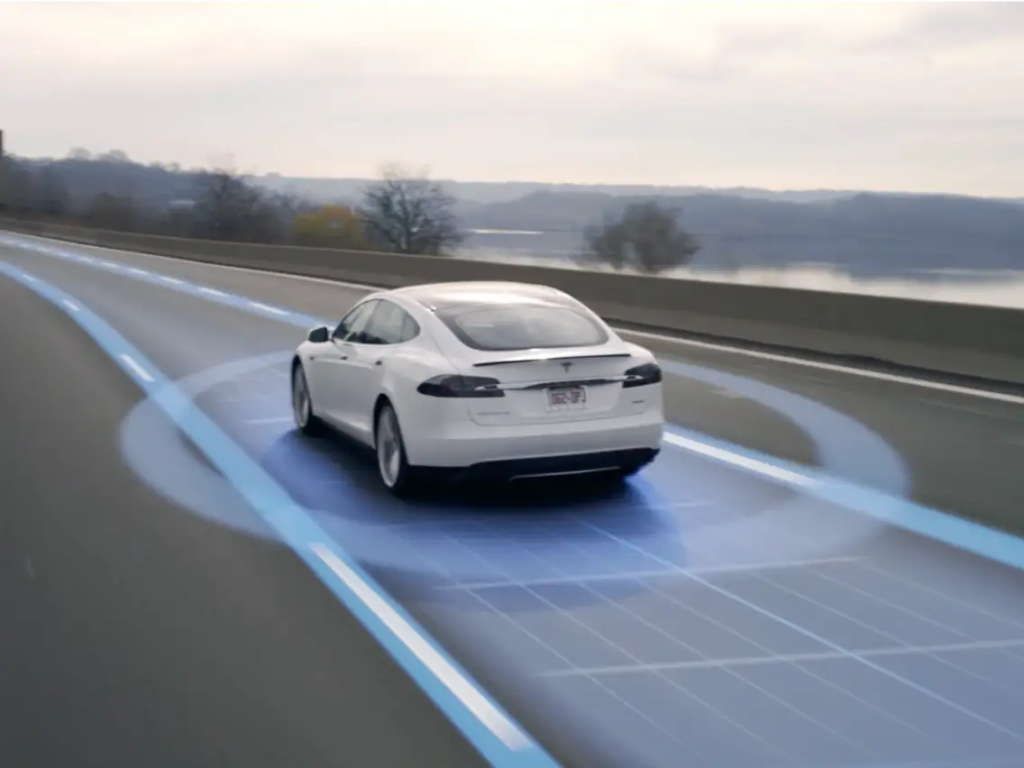

Or let’s take a more recent example: Tesla.

The trailblazing EV company launched the Autopilot driver-assistance system for its cars in 2013, and ever since then, we’ve been promised that self-driving vehicles were just around the corner.

In fact, Elon Musk has made so many failed predictions on the topic, that it has a dedicated Wikipedia page.

Many, perhaps even most, people bought into these visions because the original Autopilot was already very good. If we can teach the car to drive itself in most situations, how difficult can it be to improve it so that it can drive us reliably all the time?

The answer is: very.

In fact, the parallel between self-driving and AI is particularly relevant, since both technologies aim to teach machines to behave and think like a human being.

And it’s why AI is likely to struggle going forward just as self-driving technologies have.

It’s easy to teach a car to reliably change lanes, adjust speed or avoid obstacles in most conditions — but it’s very difficult to make it adapt to those which are less predictable and flexibly judge the changing situation on the road.

In the same way, it’s far easier to make a machine learn to mimic human speech and writing in most situations, giving it an impression of intelligence. However, it is far more difficult to actually make it think.

If you don’t trust me on this you don’t have to look far for confirmation of the slowdown in AI development — just look at the progress of the past 15 months.

How big was the leap between ChatGPT 3.5 and 4?

How many new, important features have been added in the past year? We’re 15 months into the AI revolution and yet nearly all that the “intelligent” chatbots do is the same as on day 1: summarise documents, provide simple suggestions, write or rewrite documents, answer questions, write simple code.

It’s the same among image generators, so universally vilified by artists and designers.

After initial improvements that made images they produce more usable and with the recent addition of better handling of text, their outputs haven’t exactly improved by leaps and bounds.

Most are still limited to a quite paltry resolution of 1 megapixel (1024x1024px) and have problems with accuracy or consistency.

Making that first impression of doing something out of nothing was far easier — and far more noteworthy — than spending months grinding just to make sure AI-generated humans have five fingers in each hand.

Former US president, Donald Trump, experienced it first “hand” two months ago when he posted an AI generated picture of himself praying with… six fingers on his hands.

Even after well over a year since the launch of AI image generators to the public, they are still struggling with things that are obvious and very basic to humans. Fixing them keeps consuming significant effort — quite unexpectedly, considering how we are being told that AI is about to outsmart us.

This is where AI revolution is currently at: its “grind phase”, where thousands of engineers around the world are working very hard refining things that should be fairly easy if the technology was really advanced.

Making sure the “intelligent” models don’t hallucinate, that they provide accurate outputs at all times, that they don’t mislead or insult their users. A million details that still require human sweat to get right.

Growing inputs produce increasingly smaller incremental outputs.

Yann LeCun, Meta’s lead AI researcher, highlighted the problem with the current approach upon OpenAI’s reveal of Sora, its text-to-video generating tool: it can’t really think or perceive objects, scenes, people, animals it creates.

It merely tries to accurately predict what the next pixels in the sequence should be, without understanding what it actually depicts (even if it’s remarkably convincing at it).

It’s a really compelling approximation rather than an intelligent creation — and still only a prototype that isn’t expected to launch anytime soon.

Slow is good

We’re at a point where producing smaller and smaller improvements is going to require increasingly larger investments. Such is the reality of progress in every domain of life, though (think of how much more difficult it is to set a new World Record in 100m sprint today than it was 50 years ago).

We may already be past the “wow!” moment that the launch of ChatGPT was. Every new AI service or product is likely to be less impressive, though still important and, ultimately, transformative to our lives (just like all technology before it).

The inevitable slowdown isn’t a bad sign. Quite the contrary, it’s how it has always been. The first iPhone was a bigger breakthrough than iPhone 15 but you wouldn’t trade the new one for the old one, would you?

Since we’re still in AI’s early days, we may occasionally see quite large leaps of progress, especially as the technology enters new fields.

But we also have to accept that even people who are driving the revolution say that it will require trillions of dollars and years of investments, making it one of the most expensive global endeavours ever undertaken by man.

So, we should neither be deluded by very human-like conversations with AI bots into thinking that smart androids are just around the corner, nor by the doom-and-gloom predictions of the naysayers, who claim that humanity is about to end.

We’re likely at least decades away from creating a truly thinking machine — but it’s unlikely to be the Terminator.

Featured Image: Nvidia