Long reviled as a manifesto of hate, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf has become the raw ingredient for an art project reconstituting the toxic text into something more savoury: a cookbook.

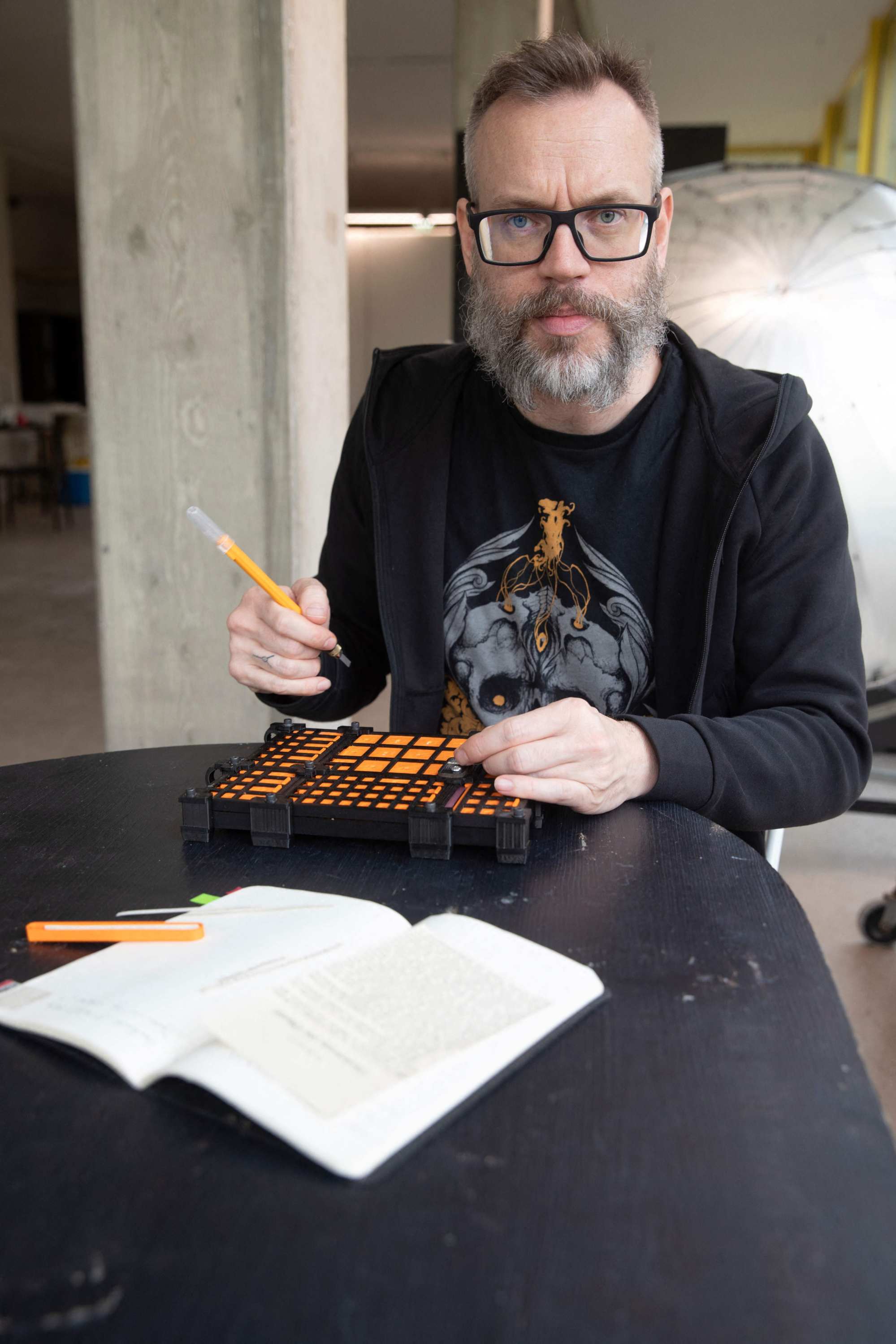

In a cafe in the late Nazi leader’s native Austria, an artist is cutting up the book that laid the ideological foundations for Nazism – its name translates to My Struggle – letter by letter and re-forming them into recipes.

The sentences are mashed and re-served as instructions for making such dishes as pizza, asparagus salad, tiramisu and egg dumplings – said to have been Hitler’s favourite dish.

Artist Andreas Joska-Sutanto has been working at it for eight years and has so far finished cutting up about a quarter of the book after almost 900 hours of painstaking work.

“I want to show … that you can turn something negative into something positive by deconstructing and rearranging it,” the 44-year-old graphic designer says in the Viennese cafe, where he can be observed once a week working for a few hours.

Published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, Hitler’s autobiographical book served as a manifesto for National Socialism (Nazism) and the ensuing wave of racial hatred, violence and antisemitism that engulfed Europe.

Venice Biennale 2024: politics, FOMO and why I’m going back

Venice Biennale 2024: politics, FOMO and why I’m going back

The book entered the public domain in 2016, when its copyright lapsed.

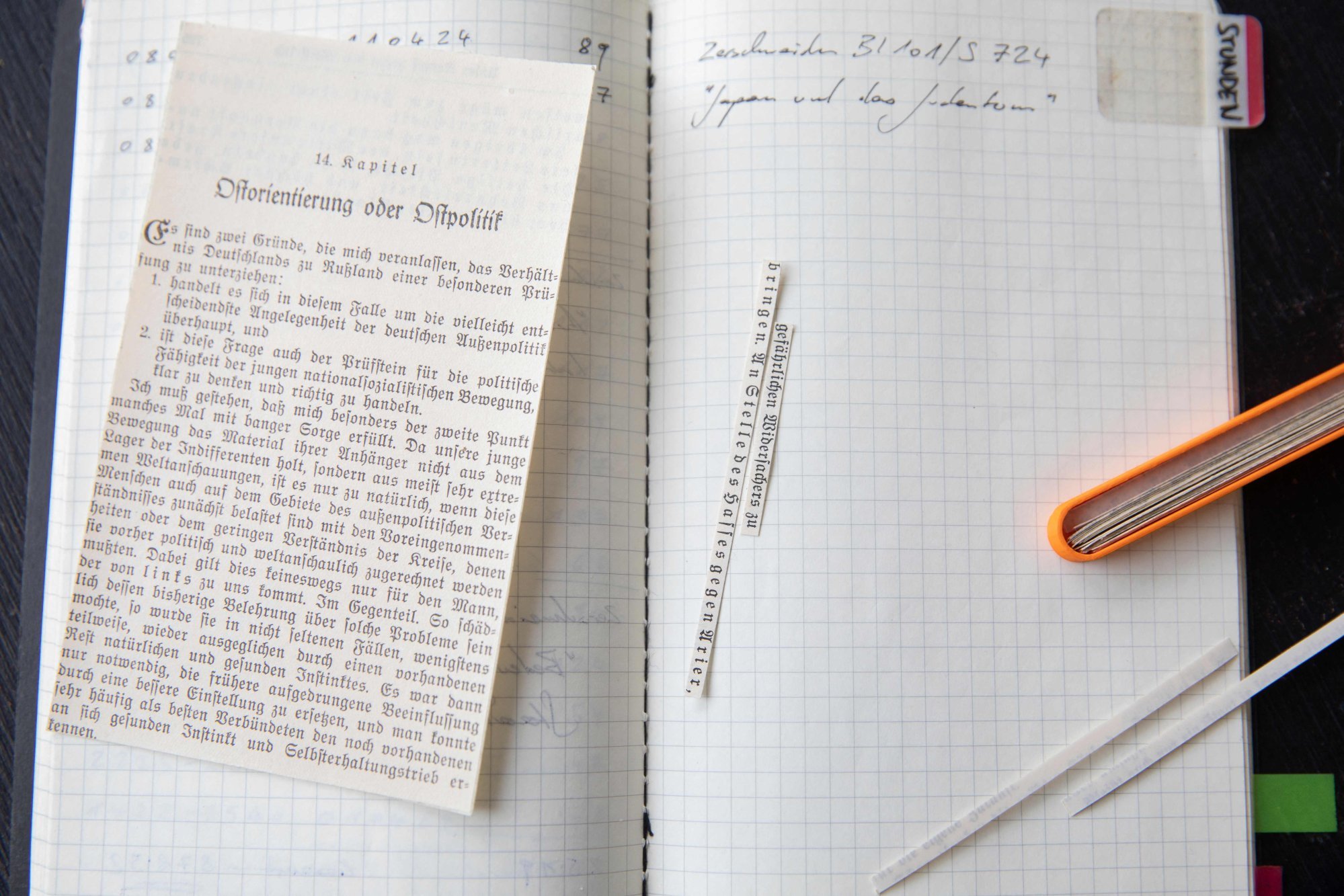

Once it became available, Joska-Sutanto came up with the idea of meticulously cutting out every single letter of the 800-page text – which has an estimated total of 1.57 million letters – to rearrange them into recipes.

He glues the pages onto adhesive film before dissecting them. So far his cookbook draft has 22 recipes.

The original text “no longer has any weight”, he said, displaying the remains of the gutted copy of the book. “All the weight in the form of letters is gone.”

He left the Nazi dictator’s portrait in the book untouched, he said, to show that “without his poisonous words” Hitler was reduced to staring at the void.

Reactions to the project have been mostly positive, Joska-Sutanto said, although he once apologised to a spectator who criticised his work as “extremely irreverent”.

At the cafe, owner Michael Westerkam, 33, praised the project – he said the raising of awareness of difficult topics such as a country’s historical past could be achieved “in many ways”.

Experts were reluctant to speak on the record about the project. One, who asked not to be named, said there was a view that it was a “strange” initiative and of “limited” historical and artistic relevance.

Austria long cast itself as a victim after being annexed by the German Third Reich in 1938. It is only in the past three decades that it has begun to seriously examine its own role in the Holocaust.

Joska-Sutanto estimates that it will take him 24 more years to finish his project.