The thing to know is that leap years exist, in large part, to keep the months in sync with annual events, including equinoxes and solstices, according to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, in the United States.

It’s a correction to counter the fact that Earth doesn’t take precisely 365 days to orbit the sun. The trip takes about six hours longer than that, Nasa says.

Contrary to what some might believe, however, not every four years is a leap year. The rule is that if a year is divisible by 100 but not divisible by 400, then it is skipped as a leap year – the year 2100, is the next fourth year that will not be a leap year.

What is a Widow Year in China and why does it matter in the coming 12 months?

What is a Widow Year in China and why does it matter in the coming 12 months?

Adding a leap day every four years would make the calendar longer by more than 44 minutes, according to the National Air and Space Museum, in the US.

The next leap years are 2028, 2032 and 2036.

Who came up with leap years? The short answer is that they evolved.

Ancient civilisations used the cosmos to plan their lives, and there are calendars dating back to the Bronze Age. They were based on either the phases of the moon or the sun, as various calendars are today. Usually they were “lunisolar”, using both.

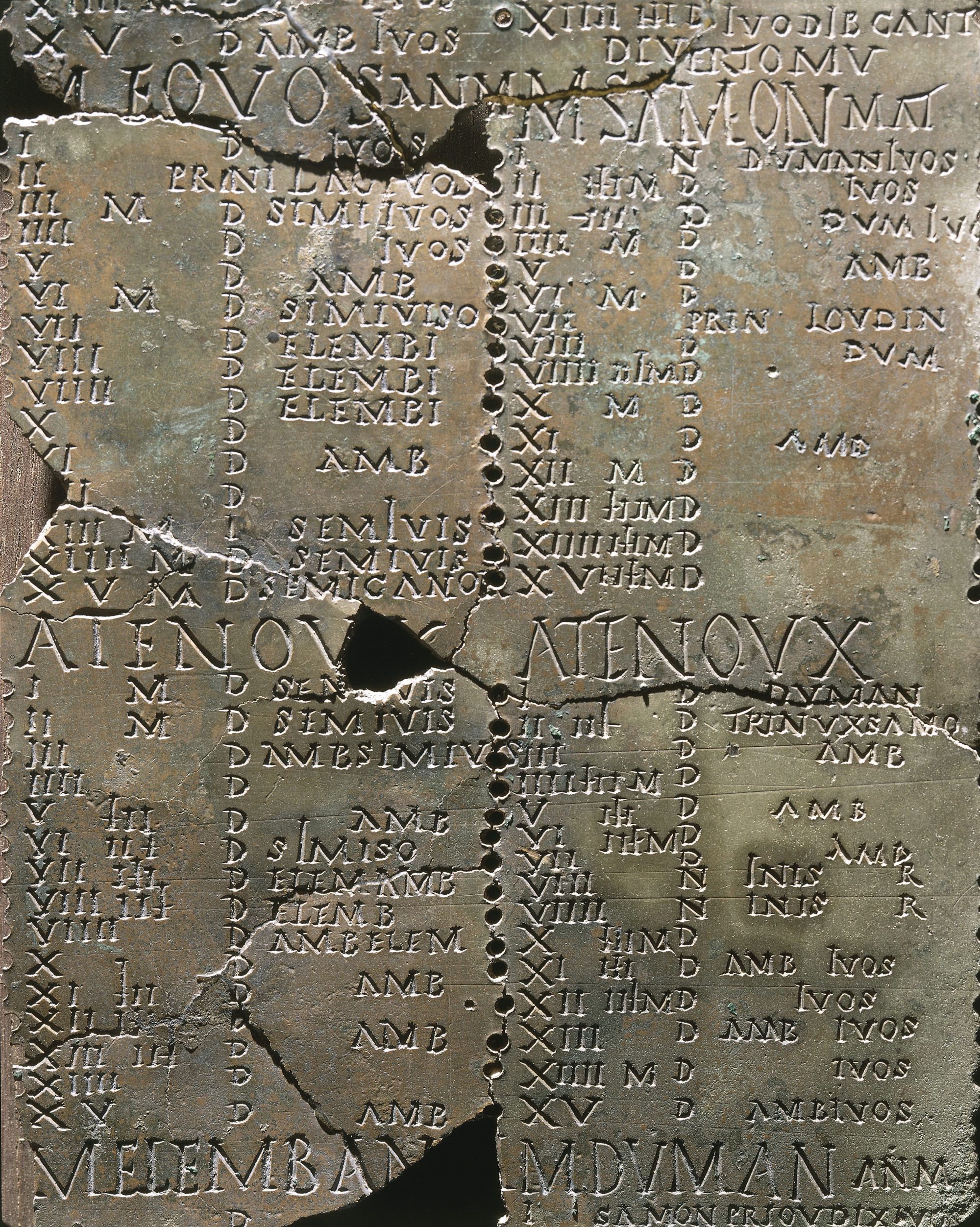

During the Roman Empire, Julius Caesar (100BC to 44BC) was dealing with major seasonal drift on calendars used in his neck of the woods. They dealt badly with drift by adding months.

He introduced his Julian calendar in 46BC. It was purely solar and counted a year at 365.25 days, so once every four years an extra day was added. Before that, the Romans counted a year at 355 days, at least for a time.

But still, under Julius, there was drift. There were too many leap years! The solar year isn’t precisely 365.25 days! It’s 365.242 days, says Nick Eakes, an astronomy educator at the Morehead Planetarium and Science Center at the University of North Carolina.

Thomas Palaima, a classics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, says adding periods of time to a year to reflect variations in the lunar and solar cycles was done by the ancients. The Athenian calendar, he says, was used in the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries, and had 12 lunar months.

That didn’t work for seasonal religious rites. The drift problem led to “intercalating” an extra month periodically to realign with lunar and solar cycles, Palaima says.

The Julian calendar was 0.0078 days (11 minutes and 14 seconds) longer than the tropical year, so errors in timekeeping still gradually accumulated, according to Nasa. But stability increased, Palaima says.

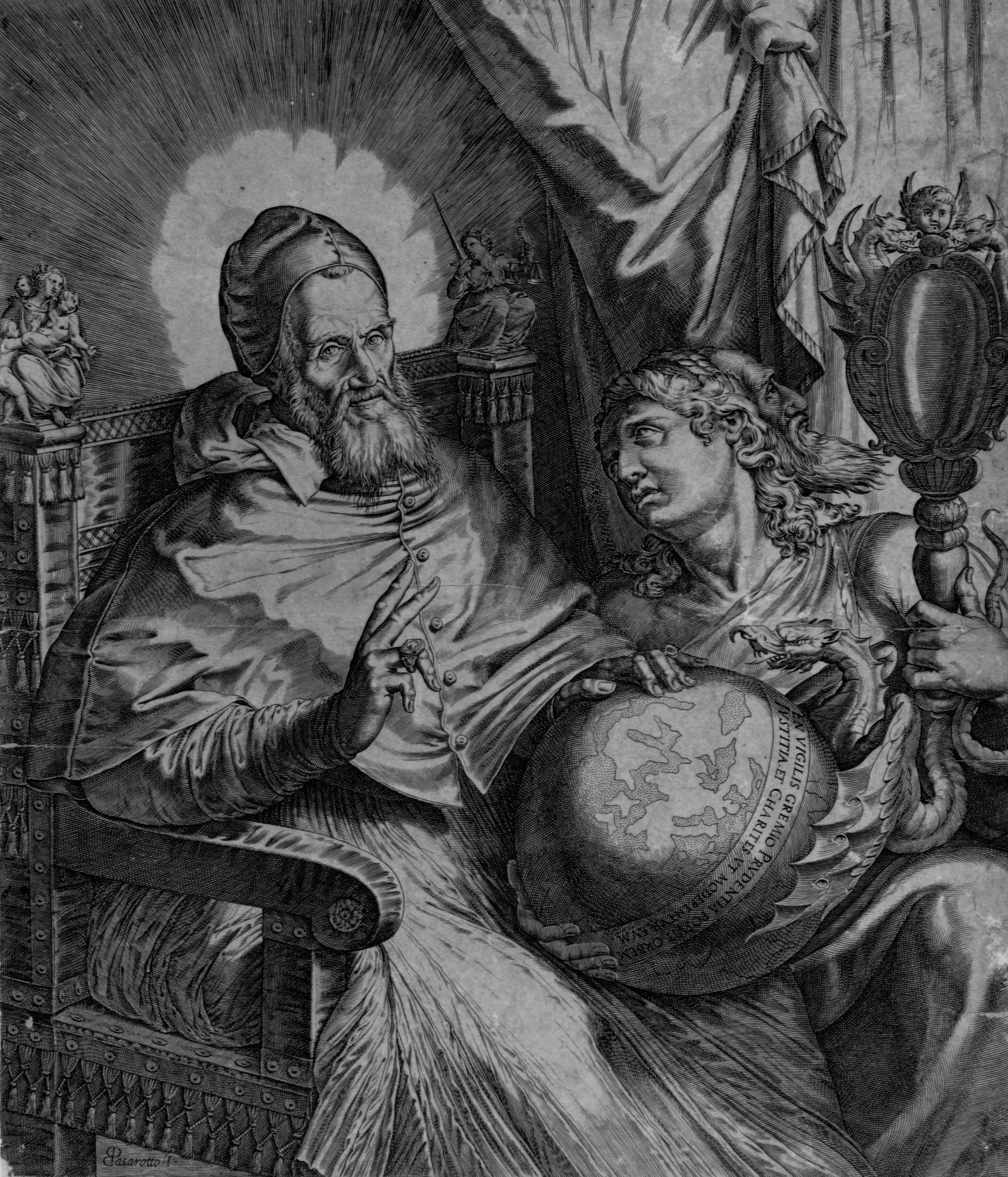

The Julian calendar was the model used by the Western world for hundreds of years. Enter Pope Gregory XIII (1502-1585), who calibrated further. His Gregorian calendar took effect in the late 16th century. It remains in use today and, clearly, isn’t perfect or there would be no need for leap years. But it was a big improvement, reducing drift to mere seconds.

Why did he step in? Well, Easter. It was coming later in the year over time, and he fretted that events related to Easter like the Pentecost might bump up against pagan festivals. The pope wanted Easter to remain in the spring.

He eliminated some extra days accumulated on the Julian calendar and tweaked the rules on leap day.

It was Pope Gregory and his advisers who came up with the maths to determine when there should or shouldn’t be a leap year.

“If the solar year was a perfect 365.25 then we wouldn’t have to worry about the tricky maths involved,” Eakes says.

Bizarrely, leap days come with lore about women popping the marriage question to men. It was mostly benign fun, but it came with a bite that reinforced gender roles.

One story from European folklore places the idea of women proposing in fifth-century Ireland, with St. Bridget appealing to St. Patrick to offer women the chance to ask men to marry them, according to historian Katherine Parkin in a 2012 paper in the Journal of Family History.

So, what would happen without a leap day?

Eventually, nothing good in terms of when major events fall, when farmers plant and how seasons align with the sun and the moon.

“Without the leap years, after a few hundred years we will have summer in November,” says Younas Khan, a physics instructor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Christmas will be in summer. There will be no snow. There will be no feeling of Christmas.”